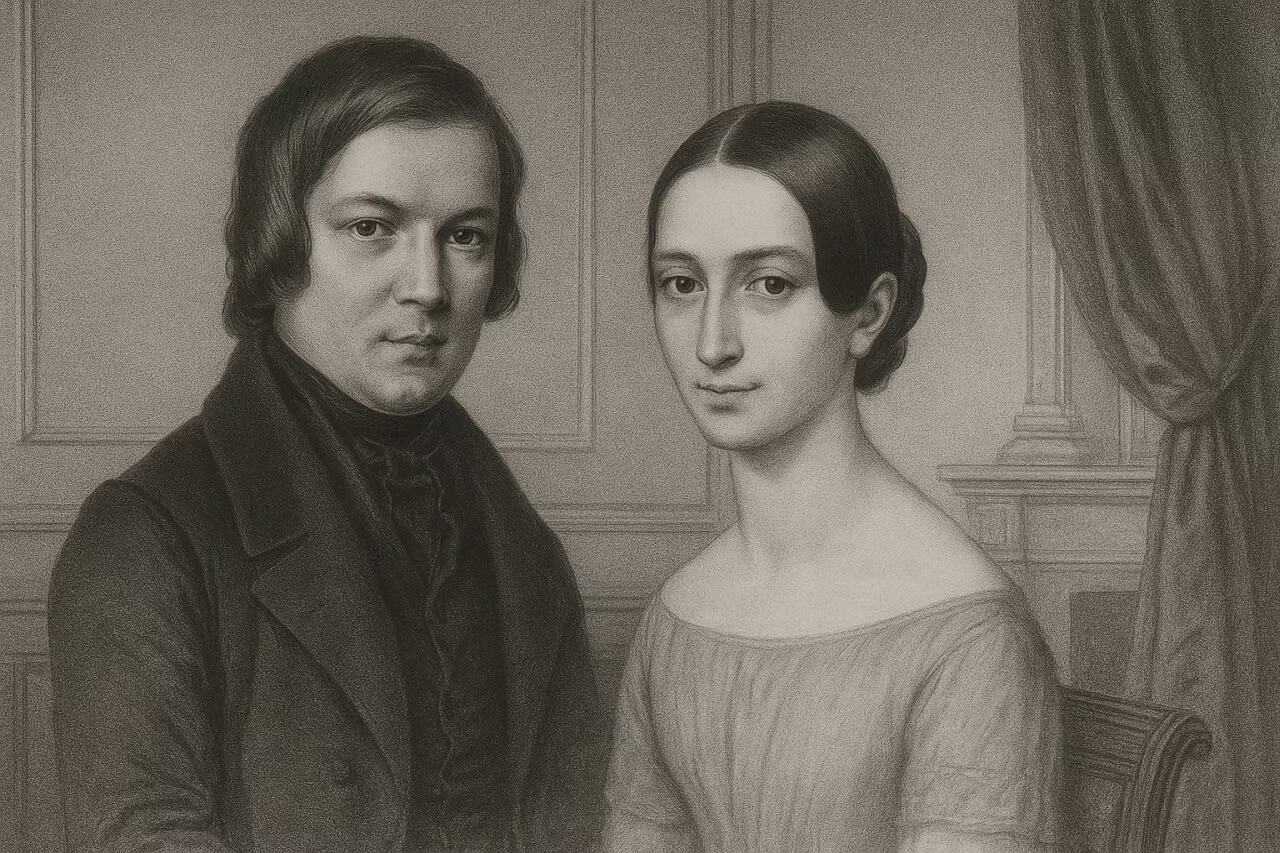

Clara and Robert Schumann: Children of the Gods of Art and the Everyday World

They lived as both an artistic constellation and a conventional family. The Schumanns embodied two extraordinary talents with Romantic souls, yet remained bound by their era. This year, the Dvořák Prague Festival presents all their concertos for solo instruments.

Composed between 1833 and 1853, their four concertos – only two for piano – are surprisingly few given their virtuosity and Robert’s later creative output. The two decades encompassed many milestones: the start of their relationship when Clara Wieck was tightly controlled by her authoritarian father, Robert’s court battle to marry her, and the strains of family life complicated by his mental instability and anxiety.

They experienced the 1848 revolution, with friends imprisoned or exiled, and welcomed the young Johannes Brahms, whose talent they immediately recognised. Clara bore eight children, the last while Robert was voluntarily in psychiatric care following a suicide attempt.

Supervision and Control

"Tomorrow I will play the Adagio from Chopin's Variations and think only of you," wrote the 14-year-old Clara to Robert. They met when she was nine and he eighteen. Clara had just finished her only Piano Concerto in A Minor, orchestrated by herself except for the first movement. She premiered it in 1835 at Leipzig’s Gewandhaus under Felix Mendelssohn.

Clara’s father, Friedrich Wieck, an influential teacher and piano expert, trained her rigorously in music, languages, theory, and what we now call arts management. His strict supervision shaped her early success but stifled her autonomy. Even her childhood diaries were partly dictated by him.

From One Hand to Another

Clara learned young that women were considered property. After her parents’ divorce in 1824, a court returned Clara and her siblings to their father, restricting their contact with their mother. Wieck strongly opposed her relationship with Robert, fearing for her financial and emotional future, but also refusing to surrender control.

Despite this, Clara outshone Robert early on, who was better known as a music critic with his Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. Her concert tours helped promote Robert’s music. Critics often praised her playing but dismissed his compositions.

They married in 1840, one day before Clara turned 21, without her father’s consent. Their marriage, idealised as an artistic union, also reflected Clara’s passage from one patriarchal figure to another. Domestic duties and motherhood curtailed her career. Clara defied conventions only modestly, yet her teenage Piano Concerto shows her potential as a composer.

One Voice in Three Personas

Robert became a leading figure among German Romantics, admired by composers such as Zdeněk Fibich. Clara’s career was curtailed by societal limits, despite talents on par with Robert’s.

His mental fragility worsened. Though highly educated, he struggled with orchestration and lasted only three years as music director in Düsseldorf. Yet the experience sparked intense creativity, resulting in works including the Cello Concerto and Violin Concerto.

Astonishingly, Robert produced around 180 major works in just 46 years. He also wrote for his journal under his name and two alter egos: the fiery Florestan and the lyrical Eusebius. His three concertos – for piano, cello, and violin – trace his marriage’s arc from bliss to psychological decline.

Piano, Cello, Violin, and a Distant Resurrection

Robert’s Piano Concerto in A Minor (1845), premiered by Clara in Leipzig under Ferdinand Hiller (later Mendelssohn), became a cornerstone of piano repertoire. Clara had just returned from a triumphant Russian tour, though travel had left Robert physically and mentally drained.

Schumann’s works rarely reflect overt despair; instead, they hint at otherworldly visions. His Cello Concerto in A Minor opens with a meditative voice amidst the orchestra, comparable to Dvořák’s own Cello Concerto, rejecting showmanship in favour of lyrical depth. Though never heard by Schumann, it now ranks alongside masterpieces by Dvořák and Elgar.

His Violin Concerto in D Minor (1853) was privately performed by the Hanover Court Orchestra. Its concertmaster, Joseph Joachim, a friend of the Schumanns and Brahms, deemed it a product of madness and never played it. Clara, swayed by Joachim, excluded it from Robert’s collected works.

Parallels exist with Bedřich Smetana’s Second String Quartet, also dismissed as "insane" before later generations recognised its beauty. The Violin Concerto resurfaced only in 1937, championed by Yehudi Menuhin, who decried its long neglect as a historical injustice.

The Schumanns at Dvořák Prague

The Dvořák Prague Festival presents all four Schumann concertos:

- Piano Concerto in A Minor (performed by Kirill Gerstein and the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden with conductor Daniele Gatti on 14 September)

- Violin Concerto in D Minor (with soloist Vilde Frang and Robin Ticciati leading the Czech Philharmonic on 19 September)

- and on 20 September with soloists Onutė Gražinytė and Steven Isserlis, Clara’s Piano Concerto in A Minor and Robert’s Cello Concerto in A Minor.

Autor: Boris Klepal